Eighth Time Lucky

What comes down has to go up at some point and oil finally managed to eke out gains after seven consecutive weekly losses in what turned out to be a rather spectacular change of heart mid-week. The stars of the bulls’ constellation started to get aligned on Wednesday when the EIA reported a meaningful draw in US commercial oil inventories, which started to look like the bullish fundamental backdrop advocated in recent monthly reports by OPEC and confirmed in its latest finding the same day. The rise in geopolitical risk premium, which has come in the form of regular hostilities towards commercial vessels in the Red Sea by Iran-backed Houthi rebels plays its indisputable part in oil’s resurrection.

Additional support arrived courtesy of central banks’, well not exactly action but rhetoric, as borrowing costs stayed put in major economies, however, US rate setters have turned dovish whilst both the ECB and the BoE made it abundantly clear that pausing is fine but cutting is off the table for now. The perceived narrowing of the interest rate gap between the US and others sent the dollar into a tailspin and its index lost 1.4% on the week. Risk appetite clearly grew, global equities rallied 2.6% and the US 10-year bond yield fell below 4%. Oil happily joined the party with WTI advancing 0.3% and Brent returning 1% on the week after a decent rally from the troughs. Sustainable? The reluctant contango in crude oil is indeed a concern but financial thirst for the black stuff could remain healthy unless bond yields and the dollar reverse course and start rising again.

A Glass, which is Half Full

Every Conference of Parties climate talk in the past 30 years has been crucial but the latest one held in the last two weeks in the United Arab Emirates bore probably the greatest relevance. It is a scientific fact that keeping the rise of global temperature at or under 1.5C of preindustrial levels is required to halt the changes in climate patterns whilst letting the increase reach 2C or higher would cause irreversible damage to the planet. The preindustrial (it is the period of 1880-1900) average surface temperature was 13.7C. Last year’s the globe was 1.06C hotter than around 130 years ago and 2023 will have proven to be more extreme. The 1.5C limit and target is getting critically close, consequently urgent action is required from all parties involved to lay down the path of limiting the rise in temperature.

Given the high number of participants (nearly 200 countries were represented at COP28) and the widely differing interest of stakeholders, success was far from guaranteed. A consensus had to be found between developing and developed countries, between oil producers and consumers, between small and big nations. One side can rightly claim that managing the climate change by phasing out fossil fuel would be akin to economic suicide for producing countries, whilst others justifiably counter that such dangers are dwarfed in significance compared to the existential threats the almost irrevocably submerging small island nations are facing. It is this backdrop against which an agreement has been reached. It is not a historic breakthrough but undoubtedly the most significant progression in the history of COPs, which keeps the hopes of mitigating the impact of global warming alive.

The central point of discussions was about the role fossil fuels, which includes coal, oil and natural gas, should play in the energy mix in coming years and decades. It was the first time that an agreement was struck to transition away from fossil fuel ‘in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with science’. There are several important points that must be emphasized: there was no reference in the draft document to phasing out fossil fuels, a tacit nod to that it will be relied upon in the foreseeable future. All countries are required to set ambitious targets to reduce their emissions by 2025 but it was acknowledged that the task will be more difficult for poorer nations than for wealthier ones. Finally, the outcome of the meeting is not legally binding, and the pledges are voluntary and cannot be enforced.

The most salient points of a non-exhaustive lists of commitments chosen arbitrarily are as follows:

Tripling the capacity of renewable energy -wind and solar and doubling the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030. The former global target chimes with the findings of the International Renewable Energy Agency, which concludes that the 2022 renewable capacity of 3,400 GW must rise to 11,000 GW by the end of the decade to limit global heating to 1.5C.

Loss and Damage Fund: this landmark deal was reached on the first day of the conference. It is intended to help the poorest and most vulnerable countries in their fight against climate change. In total, wealthy countries, including Germany, the US, Italy, France, Japan, China, and the host UAE, pledged slightly over $700 million to the fund. Critics would argue that the amount is less than 0.5% of losses incurred by developing nations from global warming.

Green Climate Fund: it was established in 2010 and it aims to support the paradigm shift in developing countries towards a low-carbon climate. It received a welcome boost during COP28 with 6 countries pledging new funding with total pledges currently at $12.8 billion.

So, will the COP28 conference ensure that the rise in global temperature will stay below 1.5C? In itself, it will not. The promise to transition away from fossil fuels is indeed an unprecedented development but gainsayers would say that the language was toned down. Pledges are vague and complying with them is not mandatory. Curiously and possibly understandably, middle-income countries stressed their need of revenues from the sale of fossil fuels to fund their transition to green energy. Given the complexity of the fight against global warming the conference was never expected to end with a breakthrough agreement. What has been achieved and agreed will not guarantee that the goal of the Paris Agreement from 8 years ago will be reached but a high level of consensus reached in the last two weeks ensures that it, at least, remains possible. The alarm clock has gone off and there is a visible realization that there is no snooze button on it.

tamas.varga@pvm.co.uk

Overnight Pricing

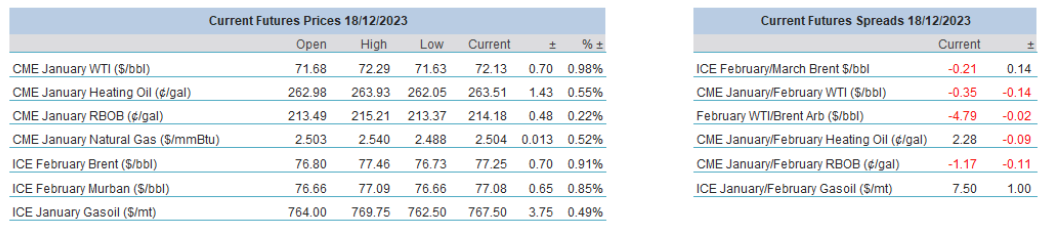

18 Dec 2023