The Fear Factor and Stock Drawdowns

Ukraine and Iran are raising the prospect of a genuine, albeit possibly short-lived, disruption to oil supply. The more imminent danger is a potential US attack on Iran, although President Trump has described the ongoing talks as constructive. Yet his patience appears to be wearing thin over the lack of tangible progress, and he has said that the next 10-15 days will determine which path the US chooses in dealing with its Middle Eastern adversary. An increasing US military presence in the region, an Iranian notice to its airmen about planned rocket launches in the southern part of the country, and Poland’s request that its citizens leave Iran immediately have all heightened investors’ anxiety.

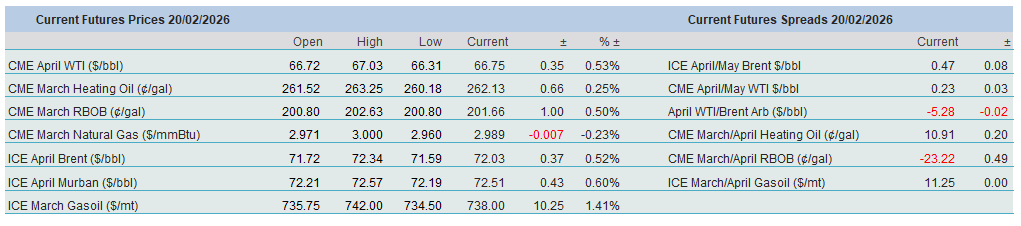

Ten days can prove an awfully long time, but the stalemate in talks has helped push Brent, WTI and Heating Oil above the upper end of their recent ranges, potentially paving the way for a further rally. For the same reason and combined with mixed US economic data, equities drifted lower. The move higher in oil was also supported by the weekly EIA report on domestic oil inventories. All major categories recorded draws, culminating in a combined 19 million bbl plunge in commercial stocks as refiners stepped on the accelerator, with proxy demand reaching 21.65 mbpd, the highest weekly reading since last July. Whatever happened to the predicted global and OECD supply surplus? Temporary or not, and we suspect the former, geopolitics and plummeting US oil stocks justified yesterday’s continuous advance. The hedge against a further rise in oil prices continues unabated.

Oil and Politics are Intertwined

There is a well-established rationale for referring to and attempting to quantify the extent of geopolitical risk premiums whenever tension flares up around oil-producing regions. Oil is a strategically important commodity, chiefly because neither its supply nor its demand responds significantly to price changes, at least in the short term. There are a few substitutes for refined products in key sectors (although the role and prevalence of existing alternatives are growing). Because of the inelasticity of oil, it is frequently used as leverage to achieve political or economic goals, and politics can also shape the supply–demand balance dramatically. Erwin Rommel lost at El Alamein in 1942 primarily because of a fuel shortage (if only he had been aware of the vast oil and gas reserves right under his feet). Saddam Hussein’s attempted annexation of Kuwait in 1990 was motivated by his desire to control his neighbour’s oil riches and cancel substantial debts from the Iran–Iraq War.

Events of the very recent past suggest that, despite the irreversible, albeit slowing, transition from fossil fuels to renewables, oil still plays a crucial role in shaping global politics. We need not go further back than January 3, when the former Venezuelan president was kidnapped by US special forces as part of the war on drug trafficking. A cynic might add that the US monopolising the Latin American country’s oil sector in the process has been a fortunate consequence of keeping America safe from fentanyl and cocaine. In any case, oil continues to shape foreign policy, and politics continues to have a tangible impact on the production and supply of black gold and, therefore, can alter the oil balance. Current events in Eastern Europe corroborate this observation.

Oil prices had been stuck in their medium-term range for nearly a month. Yesterday’s upside breakout was, according to the consensus, the result of the lack of progress in both the Ukrainian–Russian talks and the US–Iranian negotiations. The risk of further damage to oil infrastructure in Russia and a possible US military intervention in Iran, potentially leading to the closure of the Strait of Hormuz, remains elevated. However, little has been said about Slovakia and Hungary having to contemplate tapping their strategic reserves and being forced to source Kazakh, Libyan, Norwegian or Saudi oil because of an outage on the Druzhba pipeline, the main artery of oil supply for these two landlocked countries.

At the end of January, a Russian attack on the Ukrainian section of the Druzhba pipeline halted deliveries of Russian oil to Ukraine’s western neighbours. It was an undeniable blow to both countries, as the pipeline is the main and ostensibly cheapest source of crude oil for their refiners. However, it did not take long for the situation to become politicised.

Common sense would dictate that both Slovakia and Hungary protest to Russia about the supply disruptions; after all, it was Russia that carried out the strike on the pipeline. Of course, common sense and foreign policy are more often than not deemed incompatible, and when one considers the two countries’ close alignment with Russia and their anti-EU stance despite being members of the bloc, it becomes obvious that the acrimony would only deepen. Hungary, which vehemently opposes Ukraine’s EU membership, accused Ukraine, not Russia, of stopping oil flows through the pipeline, while Slovakia blamed Ukraine for intentionally delaying its restart. Hungary went so far as to suspend diesel deliveries to Ukraine as a retaliatory measure until the interruptions are resolved, notwithstanding the sizeable Hungarian minority living there.

To complicate matters, the alternative method of ensuring oil supply would be via Croatia, which cautioned against the request to transit Russian oil through the Adriatic pipeline, arguing that doing so would support and finance Russia’s nefarious war efforts against Ukraine.

The Hungarian and Slovak narrative emphasises that anything other than cheap Russian oil would jeopardise both countries’ energy security, yet the dispute between them and the rest of Europe is becoming increasingly ideological and political. Research by the Centre for the Study of Democracy (CSD) found that cheap Russian oil does not trickle down to consumers, as domestic fuel prices are almost 20% higher than those in the Czech Republic, which supplies its refiners with non-Russian oil. The CSD also found that Hungary’s dependence on Russian oil has risen to 90% since 2022, despite full access to alternative supply routes. Claims about prohibitive diversification costs are evidently unfounded: the monthly average transit fee on the Adriatic pipeline was €12.22 per tonne in 2024 for non-Russian crude, compared with €21 per tonne on the Druzhba pipeline.

Total EU independence from Russian oil appears to be impeded by political horse-trading in the above-mentioned two EU nations. After receiving a temporary EU exemption from halting Russian oil imports almost four years ago, efforts to diversify remain virtually nonexistent. Will the April election in Hungary change the status quo?

Overnight Pricing

20 Feb 2026