Gaps Still Exist in Ukraine Peace Proposal

Some things are going up in the US: the stock market, unemployment, and the prices of groceries, shelter, and healthcare. The latter category reflects bleak economic data and, ironically, supports the former. Disappointing US September retail sales and cooling investor sentiment lay bare the impact of the so-called affordability crisis, which, in turn, raises the odds of interest rate cuts next month. This, together with the strength of the technology sector, is helping the equity market. But the salient question is not if but when the cheaper cost of borrowing will reignite inflationary pressures. There is no better way to put it: the insatiable appetite for stocks contradicts the view of the Average Joe and suggests an uneven, and possibly unsustainable, economic recovery in the US.

Hopes of an eventual peace deal between Ukraine and Russia are also on the rise in Washington, D.C. The Russia-inspired 28-point draft has most likely been rewritten or at least significantly amended. The White House reports “tremendous progress” in talks with Ukraine, preparations have begun for Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s visit to the US to finalise the remaining contentious points of the agreement, and the US is sending its envoy to Russia. Yet the latest efforts to broker an agreement between the warring parties raise more questions than they answer. Are the gaps in their positions, on territorial demands, NATO membership, the size of the Ukrainian military, and Russia’s frozen assets, really bridgeable? If they are, and sanctions on Russia are lifted, oil prices will likely resume their downward trajectory. However, given the apparent chasm in ultimate objectives, could such an accord truly be called “peace,” or would it merely be a temporary agreement to stop the fighting, with far-reaching consequences for the security of Ukraine and wider Europe, the relationship between the US and its former allies, and, curiously, the unconditional admiration of President Trump by his MAGA followers and the Republican Party? This chapter of the Trump presidency has quite a few more pages to turn over.

Good COP, Bad COP

It was never going to be easy, and it was always going to be lackadaisical. The fight against global warming, although ongoing, has slowed considerably since the health crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The target set at the 2015 Paris climate conference is slipping away. Priorities have shifted, and the immediate goal of any government is to ensure energy security. The attempt to provide such security entails the continued use of fossil fuels. Renewable energy is becoming ever more prevalent; there is no denying that, but investment in oil & gas exploration and production is simultaneously on the rise. Even one of the most ardent antagonists of global warming, the IEA, considered it timely last month to align its views with reality, and it now predicts a longer-than-expected reliance on oil.

It is against this backdrop that representatives of 190 nations gathered in Belém, Brazil, over the past two weeks for the 30th Conference of the Parties to lay down a revised roadmap to slow global warming. One notable absentee was the United States. This did not come as a shock, as the current administration’s hostile stance toward climate change and intergovernmental or multilateral cooperation is frequently disseminated across various social media platforms and in the press. Under these comparatively new circumstances, talks during the conference were not expected to focus on how to halt climate change but on how to adapt to it.

Although the conference made clear from the outset that global problems cannot be solved by prioritising national interests, to put a positive spin on the outcome of COP30, there was something for everyone. The good news is that there was a deal in the end. However, it included no direct reference to fossil fuels. The UK and the EU, among 80 other countries, were keen to strike an agreement that would have embraced a plan to phase out coal, oil, and natural gas. The counterargument came from producers, who insisted on the need to utilise their resources; otherwise, their economies would suffer an unfair disadvantage. Saudi Arabia, for one, argued that “each state must be allowed to build its own path, based on its respective circumstances and economies.” Conversely, Colombia pointed to “sufficient scientific evidence” showing that fossil fuels are responsible for more than 75% of total greenhouse gas emissions. In the middle were countries such as Antigua and Barbuda, whose climate ambassador was simply content that talks were taking place at all.

While acrimony and heated exchanges characterised the latest climate summit, talks centred around three main areas: fossil fuels, finance, and nature. At COP28 in 2023 in the UAE, there was a consensus on the need to transition away from fossil fuels. Although several participating countries pushed for strengthening this commitment, they encountered resistance from fossil fuel producers. In the end, the deal made only a passing reference to the UAE agreement and did not reinforce the pledge to move away from fossil fuels.

On the finance front, the final agreement called for tripling the funds for those most affected by climate change. It is worth recalling that COP29, held in Baku last year, promised to make at least $300 billion per year available for more exposed nations, who claimed that the amount was significantly lower than needed. It is, nonetheless, unclear how much of the new tentative commitment of $1.3 trillion, expected to be mobilised for “climate action,” will come from public versus private sources.

Ahead of COP30, the host country, Brazil, launched an initiative to halt the loss of tropical forests. It would reward countries that preserve their forests. Over $5.5 billion was pledged to the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) by 53 countries, with the aim of raising $125 billion from loans and investments. The host nation announced a roadmap to halt deforestation, a pledge first made at COP26 in Glasgow. This roadmap, however, did not make it into the final deal.

This mixed bag, which boosts climate finance but provides no concrete steps to phase out fossil fuel consumption, can be viewed as a faithful reflection of the headway (or lack thereof) made in the transition. The shift is irreversible, although reliance on fossil fuels will be more protracted than anticipated. The Paris climate goal of keeping global warming 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels will not be achieved, but it is useful to take a broader view. After the disastrous COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, climate scientists warned of a dire and suicidal warming trajectory of as much as 4°C based on then-current policies. The contemporary estimate, relying on conditional pledges and significant financial support, is around 2.3°C, higher than the Paris target but lower than the Armageddon-like prognosis of 16 years ago. Progress, right?

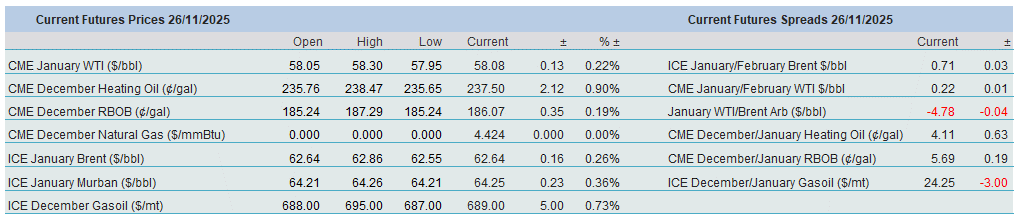

Overnight Pricing

26 Nov 2025