If it’s madness, is there a method to it?

Those with ample time on their hands were treated to almost three hours of Donald Trump over the past two days: one hour and forty minutes on Tuesday, marking his first year in office, and around one hour at the World Economic Forum in Switzerland yesterday. Both were astonishing to watch and listen to. They were full of unsubstantiated claims (“ending eight wars”), obsessions (the Nobel Peace Prize), assumptions disguised as objective realities (“only the United States can protect Greenland”), as well as insults, untrue assertions (“Somalia is not a country”), and disturbing confusion (he referred to Greenland as Iceland four times).

Embarrassing performances, slick business tactics, or political brinkmanship? That is open to interpretation. One thing, nonetheless, appears obvious: US foreign policy is the source of systemic risk. This geopolitical risk—or, as so eloquently put by the Financial Times, “ego-political” risk—surrounding Greenland and threatening to revive a trade war between former allies was the reason investors deserted equities on Tuesday. The key takeaway from Trump’s speech in Davos was an ostensible climbdown in narrative, ruling out the use of military force to occupy the island. It was, however, the previous day’s climbdown in share prices that led to the more emollient tone. One should not kid oneself: the high correlation between US stock-market performance and bellicose US foreign policy will persist, notwithstanding yesterday’s correction in equities. And even if the Greenland deal holds, will other countries, such as Canada, face any danger of being occupied, given Mr Trump’s ambition to go down in history as the President who expanded the US territory?

Stocks have rallied, clawing back around half of Tuesday’s losses, and will probably continue to do so today, as the imposition of new tariffs on European countries has been suspended following the announcement of a “framework agreement” with NATO on Greenland. Is the hatchet buried again? This is what puzzles politicians and investors alike; heads are spinning, eyes are rolling, laughs are fake, but the tears are real.

In these extraordinary times, oil investors did what seemed most reasonable: they reacted to developments in their market that could affect the oil balance. The morning dip, possibly triggered by the monthly IEA report discussed below, quickly turned into a semi-decent rally, sparked by a force majeure declared by the operator of Kazakhstan’s Tengiz oil field, disappointing Venezuelan oil exports, and seasonal strength in distillates. The CME front-month Heating Oil contract has gained more than 10% in less than a week due to cold weather, lower stocks, and ongoing Ukrainian drone attacks on Russian oil installations. Yet the dark cloud of oversupply hangs over the market, as also confirmed by the post-settlement API report, which showed considerable builds in crude oil and gasoline inventories.

The IEA remains the most pessimistic

Last week, after both the EIA and OPEC published their updated reports on the global oil balance, we established that there are both similarities and differences in their views. They agree that global and OECD commercial oil inventories will swell year- on-year. In fact, based on their latest findings, every single quarter of 2026 will experience growth in stockpiles worldwide as well as in developed countries. There was also consensus on demand growth and non-OPEC+ supply growth. Both expect the former to outpace the latter, resulting in an increase in DoC calls.

So, while the trends identified by the two forecasters are broadly aligned, the absolute figures diverge wildly. The EIA expects a year-on-year build of 215 million barrels in OECD oil inventories in 2026, reaching 3.146 billion barrels by year-end. Conversely, OPEC envisages the end-2026 figure at 2.981 billion barrels (assuming an annual DoC supply of 43.95 mbpd), representing an annual rise of just 142 million barrels.

The IEA joined the other two forecasters and published its own numbers yesterday. The energy watchdog of the developed world has traditionally been the most pessimistic of the three, although it should be noted that its rather downbeat demand estimates, largely a function of its expectations of a comparatively faster transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, have begun to converge with those of the other two, particularly OPEC. Its 2026 global oil consumption estimate, for example, has been upgraded by more than 700,000 bpd between April last year and this month.

This adjustment, while reducing the previously unprecedented schism between the IEA and OPEC, still leaves the agency lagging significantly. In its latest report, 2026 demand growth has been revised up from 860,000 bpd last month to 930,000 bpd. Even so, a 1.6 mbpd gap remains in global consumption projections: OPEC places it at 106.55 mbpd, while the IEA estimates 104.95 mbpd. Notably, this difference exceeded 2 mbpd just nine months ago.

Although demand levels and demand growth estimates have been revised higher, the IEA remains the only forecaster that expects non-OPEC+ supply to increase faster than global oil consumption. As a result, its view on the OPEC+ call diverges markedly from the others. It sees the call falling by 570,000 bpd in 2026, compared with increases of 880,000 bpd and 680,000 bpd projected by the EIA and OPEC, respectively.

The IEA estimates demand for OPEC+ oil to average nearly 2 mbpd below the EIA’s call and 2.85 mbpd below OPEC’s projection. This gap has an enormous impact on projected global and OECD stock changes. All three agencies foresee global, and OECD stock builds in every quarter of the coming year, but the magnitude differs substantially: 880,000 bpd according to OPEC, 2.84 mbpd according to the EIA, and 3.72 mbpd according to the IEA.

This, in turn, has a profound effect on OECD stock estimates, which by year-end range from 2.966 billion barrels (OPEC) to 3.146 billion barrels (EIA) and as high as 3.381 billion barrels (IEA). At this point, we would like to reiterate that we assume a 4-barrel change in OECD stockpiles for every 10-barrel swing in global oil inventories.

Although there is consensus that oil inventories will swell this year, the differences in outlook are vast by any standard. When we compared the EIA and OPEC projections in last Friday’s report, we calculated, based on OPEC’s numbers, that Brent should average around $8/bbl below the 2025 mean of $68.19/bbl. This was predicated on end-of-year OECD stocks of just under 3 billion barrels. Replace that assumption with the IEA’s estimate outlined above, and the implied year-on-year discount balloons to more than $25/bbl.

While in an unreasonable world, nothing can be ruled out, the current futures curve indisputably disagrees with such an extreme outcome. Do we dare draw a conclusion? If so, it would be that expectations are rising for the IEA to further align its global oil demand estimates with those of the other forecasters.

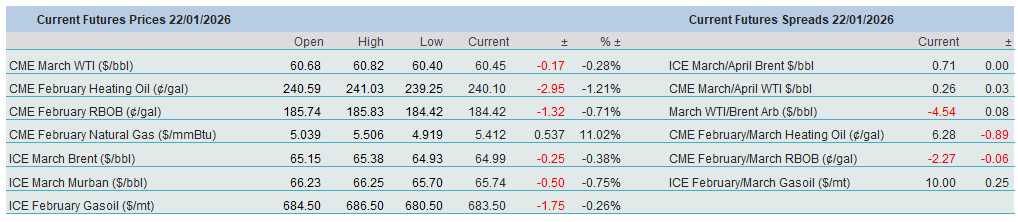

Overnight Pricing

22 Jan 2026