Markets are Always Right

Without any schadenfreude, a spade needs to be called a spade. Markets spoke, bonds the loudest, and it led to a capitulation in its purest possible form, a partial one, anyway, regardless of how it has been spun and sold. And yet, in this tacit admission of miscalculation, the message was characteristically vague and confusing. President Trump announced a concurrent 90-day pause of ‘reciprocal’ tariffs and a lowering of them to 10% for most trading partners. Understandably, markets rallied, the Nasdaq Composite Index 12% on the day and oil 13% from low to high. The relief was palpable but worries persist. Will it really be 90 days? Or maybe 5 days or perhaps 2 years? Will it really be 10% or will it be upped to 20% in a few days? And lest we forget the great and stubborn nemesis, China, who has to live with an exorbitant punitive import tax for now with potentially grave economic consequences. The extreme tariff market between the two juggernauts is presently 84% bid at 125%. It is probably reasonable to stop here and not delve into the fine details because this fluid situation will undoubtedly change for the better or the worse. However, the key takeaways of the U-turn are the additional loss of credibility of the administration and the continuous prevalence of uncertainty amongst investors.

Whilst on a Thursday it is almost mandatory to mention that US commercial and crude oil inventories built despite hefty drops in major product stocks and that the Keystone pipeline remains shut, these usually salient developments are dwarfed by the latest twist in the tariff saga. It is, therefore, a timely exercise to sum up the steps that might have led to yesterday’s spectacular reversal.

The Many Definitions of Fairness

Ripping up the order global trade was based on before President Trump started his second term is sending shockwaves throughout markets. Risk assets have been in a freefall. Investors’ sentiment was grim before, just think of the 2007-2009 financial crisis or the Covid-induced Armageddon. This time it is different. During past crises, we knew what was happening and why. We knew that reckless lending caused equities to fall 18 years ago, and we were fully aware that the global lockdowns paralyzed economies in 2020. In both cases measures, whilst fiercely debated, were transparent and one was able to make sound judgements and plan ahead. This time, the length and the outcome of the trade war ignited by the US are ambiguous, and the direction it will take is unpredictable. It is partly a crisis of confidence and uncertainty is worse than pessimism.

In all honesty, the US has a point. Tariffs, which are meant to protect domestic economies can be unfair. It is a fact that the US, in the past, charged lower import taxes than its trading partners. It is this uneven playing field that the US is attempting to level. According to an FT opinion piece by Peter Navarro, President Trump’s senior counsellor for trade and manufacturing, ‘All America wants is fairness. President Trump is simply charging you what you are charging us. What is fairer than that?’

The argument sounds undisputable, but the original strategy questions the idea of fairness. Why should Australia suffer from a 10% tariff when the US runs a trade surplus with them? The answer is, because of the banning of beef imports from the US to Australia due to BSE detected in US cattle. Or a 10% punitive tariff on, say, Colombian coffee imports, which makes no economic sense whatsoever because the US is not a coffee producer. It also shows a lack of fairness, chiefly towards the US consumer, who pays the price for rejecting the axiom of comparative advantage – you let other countries produce what you are not good at producing but what is in demand by your consumers. On a side note, one must not forget the very existence of US agricultural subsidies, which are the equivalence of unfair tariffs against countries bilateral free-trade agreements were signed with.

Tariffs are meant to bring manufacturing back home and they also help pay for the tax cuts that are being implemented. This is, again, flawed logic. It is impossible to increase government revenues by imposing high punitive measures and at the same time re-ignite the manufacturing industry (which carries dubious benefits, as the service sector now weighs more heavily in economic prosperity). Higher tariffs are impediments to the revival of the manufacturing sector.

And there is the question of trade deficit. It is loosely linked to import tariffs but undoubtedly not synonymous with it, although the official narratives suggest otherwise. Tariffs hamper imports and, therefore reduce the trade gap but when they entail retaliation, it defeats its original purpose. Trade deficit is a clear sign, the argument goes, that the US ‘has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered’ by other countries. Well, the US stock market comfortably and confidently outperformed the rest of the world until a month ago, not exactly a sign of coordinated economic insult against it. One of the golden eras of Greek economic growth was the early 2000s when the country was running a significant trade deficit. Why? Because investors found it attractive after the introduction of the euro. Negligible US saving, which supports aggregate demand and consumer spending also incentivizes imports.

Disproportionately high tariffs historically imposed on the US are unfair, particularly from China, which often violates global trading rules and exports its surplus capacity. It, however, does not mean that the difference can be rectified by blanket tariffs or by a formula, which has nothing to do with reciprocity. Negative trade balance is not a disadvantage, especially not for the US, which controls the world’s most crucial reverse currency and as such it raises inevitable barriers for its own exports in return for using the dollar as a weapon in geopolitical and economic disputes.

The US Administration’s attempt to rewrite the global trade book appears more harmful than beneficial, more so for the US than for the rest, apart from China. Yesterday’s volte face vindicates this view and shows that the impact of tariffs in their proposed form is akin to the activity of a bull, well, probably a bear, in a China store. It poses an unbearable headache for the Fed, too as it must decide whether to cut rates to aid economic growth and avoid recession or increase it to fight inflation. Again, this uncertainty does favour to no-one. Even considering yesterday’s mitigative announcement, it is not clear how far the Trump apparatus is willing to go to fight this seemingly senseless war. Maybe the stock, or possibly the bond markets are, in fact, the ultimate check and voters’ dissatisfaction might also act as a brake on confrontational policymaking. If not, recession, inflation, and stagflation are the soundbites we will keep hearing frequently.

Overnight Pricing

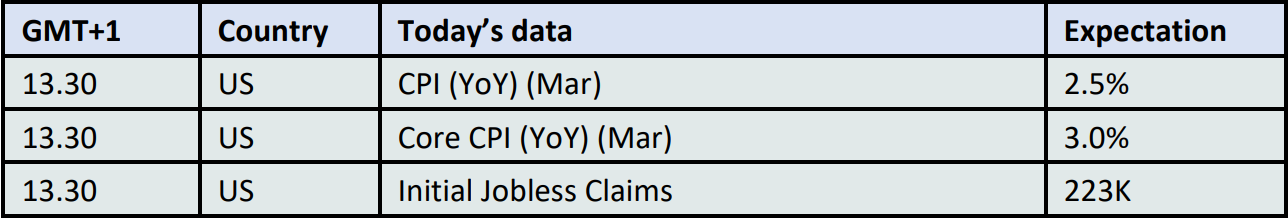

10 Apr 2025