Ukraine’s Price Support Might Wane Soon

Beyond a verbal slap on the wrist, the recent hideous Russian attack on the Ukrainian capital, which claimed the lives of at least 21 people, including four children, was met with deafening silence from allies and the US. Sanctions on Russia remain elusive; reciprocal atrocities, therefore, are likely to continue. Given the effectiveness of Ukrainian drone strikes against the invader’s refineries, Russian crude oil exports should rise, while product sales move in the opposite direction. Reuters estimates that idled Russian refinery capacity now stands at a record high of 6.4 million tons. That is an awful lot of products off the market.

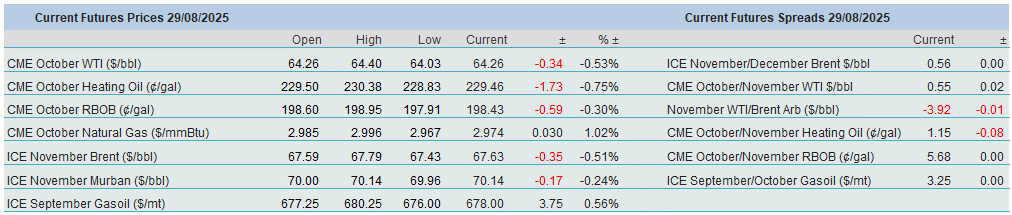

These assaults, a key source of support for oil prices, cannot be sustained indefinitely, and once Russian refiners return online, prices may begin drifting lower again. Punishing India by doubling trade tariffs could turn out to be a nothingburger, as the world’s most populous country is reportedly preparing to ramp up its purchases of Russian crude oil by 10%–20% next month, both in defiance of unilateral US sanctions and in pursuit of irresistible discounts. It is also noteworthy that refiners’ demand for feedstock may be declining, as reflected in the perceptible retreat of Brent CFDs. Current backwardation on both Brent and WTI also sits well below the levels seen a month ago. Increased OPEC+ production and massive PG spare capacity also provide comfort for those anxious about protracted supply disruption.

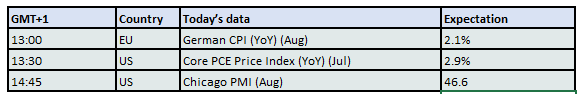

Although the influence of equities on oil has been dwindling for several months, the resilience of the stock market continues to provide tacit support. As investors digested quarterly results from chipmaker Nvidia, the S&P 500 index quietly snuck higher to yet another record peak, buoyed by a rebound in second-quarter corporate profits and fewer-than-expected jobless claims. The CME FedWatch tool still places the probability of a September rate cut at around 85%. Today’s release of the crucial PCE Price Index could either bolster sentiment or sour the mood. The magic number is 2.9% on a core basis, and any reading above it will likely trigger a stampede towards the exits of equity and bond markets.

Short and Long-term Impacts of Interventionism

The norm-busting governance of the incumbent US administration needs no introduction. Numerous examples have emerged during the first eight months of the second Trump term, including the crackdown on immigration, unprecedented pressure on the central bank, unilateral trade tariffs on foes and allies, and the decimation of USAID, to name a few. These measures can be criticised or welcomed, depending on one’s taste and values, but what is interesting, and even disturbing, to observe is that they are mostly legal. Those that are not will likely receive the nod from a sycophantic Congress or a pliant judiciary. There is no law against governing by executive order, cancelling aid to sub-Saharan African countries, greeting an indicted war criminal on US soil, accepting pro bono work from several law firms, or accepting a gift of a plaque with a 24-karat gold base from the CEO of a tech company, let alone a jumbo jet from a foreign state.

President Trump pushes the boundaries of executive power almost daily with relative success. Although his approval rating is below that of Barack Obama or Joe Biden at the same point in their presidencies, it appears to be stabilising. Markets, judging by the performance of equities and the resilience of bond yields, are taking an even more favourable view of the President’s achievements. The latest unorthodox move, increasing intervention in the economy by acquiring shares in several companies, has not changed this perception.

Traditionally, the Republican Party has been a staunch advocate of free markets, supporting supply-side economics, deregulation, lower taxes, and as little state intervention in corporate America as possible. On a rhetorical level, the US president also remains an unconditional ‘free trader.’

Of course, intervention is sometimes desirable and even inevitable, such as during economic hardships or on national security grounds. The 2008-2009 financial crisis is a striking example of the former. The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) injected significant capital into banks, insurance companies, and car manufacturers. The combined aid provided to General Motors, Chrysler, AIG, and Citigroup amounted to $289 billion; however, these shares were sold back to the market after the crisis passed, yielding a net profit of $22.9 billion for the taxpayer. Losses on the carmakers were dwarfed by profits from AIG and Citigroup.

This time, however, no apparent crisis is brewing, at least not on the surface. The Nasdaq Composite Index is just shy of its all-time high and has returned 47% since its ‘Liberation Day’ trough. Yields on 10-year bonds also remain significantly below their peak of 4.59%, recorded on April 11. Yet, the growing interest of the US government in acquiring shares, or at least demanding a portion of the revenue from several US corporations, is impossible to ignore.

Nearly three months ago, the government approved the takeover of US Steel by Japan’s Nippon Steel in exchange for a “golden share,” despite the Biden administration’s earlier rejection due to national security considerations. In July, the Pentagon became the largest shareholder in MP Materials, the country’s only rare-earth producer. Soon after, Nvidia and AMD were allowed to resume chip sales to China, previously banned on security grounds, in return for 15% of revenues. Just last week, the government announced the acquisition of a 10% stake in Intel, worth $8.9 billion. The deal raised eyebrows from some corners, to which the President responded on social media: “I would make deals like that for our Country all day long,” implying that such transactional policymaking has become the zeitgeist of his administration.

Government interventions can be justified on national security grounds. Proponents point out that, given the perpetual rivalry with China, the Intel and MP Materials deals appear reasonable. It is a fair reflection, nonetheless, the quid pro quo deals with Nvidia and AMD will likely weaken the US position against China in the field of AI and show inconsistency in economic policy-making.

On a practical level, this idiosyncratic interpretation of free markets presents two problems. First, it provides unfair advantages to chosen companies over their domestic competitors; cronyism typically leads to corruption and stifles innovation. Second, one cannot help but conclude that increasing government intervention, state ownership, and general interference in market forces serve the immediate purpose of reducing the ballooning national debt, similar to the pressure on the US central bank to cut interest rates steeply and fast, regardless of the enduring repercussions.

History offers caution. The seven-decade experiment with full government control of the economy, from 1910 to 1990, ended in failure. To compare today’s US economy with a centrally planned system would be grossly unreasonable and misleading, yet the adage from dissidents in former communist states, the state is the worst owner, rings true. Government intervention can protect national interests in times of crisis, but when wielded for short-term political gain, it is bound to produce medium-term economic pain.

Overnight Pricing

29 Aug 2025