Weak Dollar, Strong Distillates

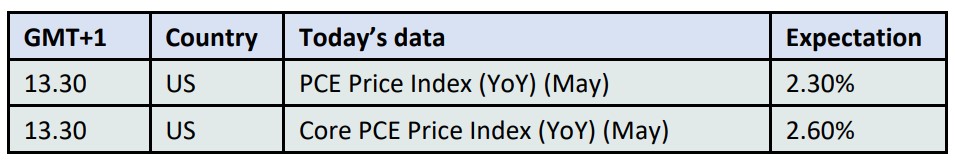

After striking a truce in the Middle East, the U.S. President wasted little time in turning his attention back to his favourite antagonist in Washington D.C., the Fed Chair, Jerome Powell. He is reportedly contemplating choosing Powell’s replacement well before the latter’s mandate ends in May next year. Concerns over the central bank’s independence have resurfaced, and the dollar index has plunged to its lowest level since March 2022. Mr. Powell has consistently argued that any potential reduction in U.S. borrowing costs will be data-driven—an approach Donald Trump clearly rejects. In any case, as a growing number of Americans remain on unemployment benefits and continuing claims hit their highest level since November 2021—despite weekly initial claims falling—a rate cut could come as early as July or, more realistically, in September, according to the CME FedWatch tool. The Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index, to be released this afternoon, could hasten the process — if the core figure does not exceed the forecasted 2.6%.

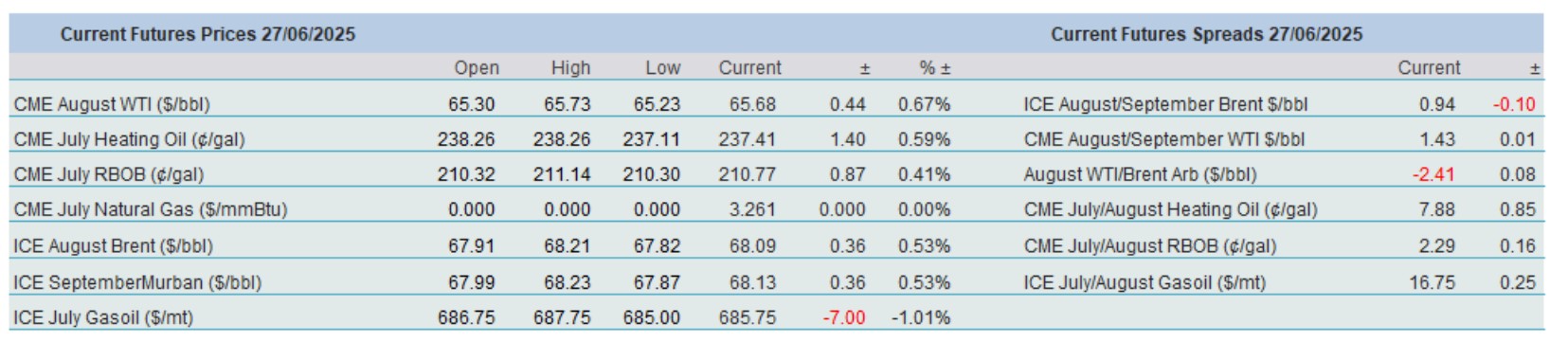

While the weak dollar may have offered some support to oil prices, the real driving force behind yesterday’s resolute performance was a series of oil inventory reports, particularly those concerning middle distillates. We noted the 4 million-barrel weekly drawdown in U.S. distillate stocks in yesterday’s commentary, but signs of a global tightness in the middle of the barrel are becoming more apparent. In the crucial ARA hub in northwest Europe, gasoil stocks plunged 10% week-on-week, according to PJK International. In Singapore, middle distillate inventories fell by 900,000 barrels—or 8%—nearly matching the European decline. As a result, Heating Oil lent support to the entire oil complex. Our outlook on a looser second-half oil balance, based on monthly reports, has not changed. However, scrutinizing these weekly stock updates will be pivotal in identifying any trend reversals.

Oil is Becoming less Intense

Circling back to yesterday’s report, it is becoming increasingly evident that the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy is irrevocably underway. As nearly every piece of research, analysis, and forecast suggests, this does not imply a falling demand for oil. Although projections for future oil consumption can vary significantly, the absolute figure continues to rise. Depending on which perspective one adopts, this growth could persist for the next decade or two. Nonetheless, the role of fossil fuels in the overall energy mix is declining, as demonstrated by the growing use of alternative energy sources—such as wind and solar—and the widespread adoption of electric vehicles.

Another approach to measuring the relevance of oil is to compare its consumption to produce one unit of GDP, in other words, oil intensity. This measure shows a small but perplexingly steady decline for the past 50 years, which is expected to hasten as the fight against climate change intensifies. The use of oil to produce $1,000 of GDP, in 2015 prices, peaked in 1973 when slightly more than 1 barrel of oil was required to generate $1,000 worth of goods and services. Cheap oil and rapid industrialisation were driving consumption. From the second half of the 1970s, apart from a 2-year upside blip between 1975 and 1977, the trend has been reliably downward. In fact, it was the Arab oil embargo of 1973 and the 1979 oil shock that made attempts to achieve efficiency gains an almost inevitable phenomenon. By 2019, just before the pandemic broke out and the last year we were able to gather data, global oil intensity fell to around 0.43 barrels per $1,000 GDP.

From the 1980s through the early 2000s, the major catalysts for the improvement in oil intensity included efficiency gains in vehicles, manufacturing and power plants, economic restructuring in the developed part of the world and technological improvements. Those who have spent at least two decades in our industry still recall the structural bull market seen at the beginning of the third millennium, which ended when the US subprime crisis nearly devastated the global economy. It was the period of the rise of China (and to a lesser extent India), with the former joining the World Trade Organisation, pushing the price of oil near $150/bbl. Increased oil demand briefly and almost invisibly elevated intensity but untamed oil prices were the ultimate force to spur efficiency gains.

In the last 10-15 years, the global, though largely uncoordinated, attempt to reverse or at least stop the rise in global temperatures can be added to the list of factors that have been constantly improving oil intensity. The widespread electrification of transportation, which has been the major consumer of oil, the prevalence of renewables in power generation, the focus on sustainability and the birth of artificial intelligence have all contributed to the increased optimisation of oil use.

According to the Centre on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, oil intensity, or the dependence on oil, if you will, fell by 56% between 1973 and 2019. This pattern, the authors of the paper observed, shows that oil intensity fell in a nearly linear fashion since 1984 despite geopolitical events, economic recessions and recoveries and the significance of OPEC in shaping the oil balance and therefore prices.

This kind of regularity, the study concludes, is a rare phenomenon in any long-term economic or energy trend. Yet, here we are, our dependence on oil has been on the decline for 50 years, come hell or high water, and this trend is likely to persist. Absolute oil demand will most plausibly keep rising, just as it doubled between 1973 and 2019, whilst oil intensity halved. After all, the world’s population will keep growing, and consequently, the global economy will keep expanding. However, technological and scientific advances, efficiency gains and the shift to alternative energy will keep reducing our reliance on oil as a percentage of total energy demand. The key difference between the past and the future will be a slowing rate of oil demand growth and an accelerating transition away from the black stuff.

Overnight Pricing

27 Jun 2025